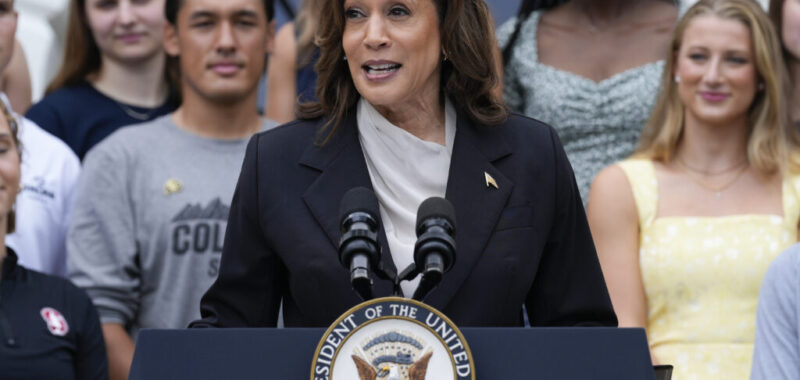

Vice President Kamala Harris speaks from the South Lawn of the White House in Washington on July 22, 2024, during an event with NCAA college athletes. This is her first public appearance since President Joe Biden endorsed her to be the next presidential nominee of the Democratic Party.

Credit: AP Photo / Susan Walsh

The likelihood that Vice President Kamala Harris will be the Democratic nominee for president is inviting scrutiny of her positions on every public policy issue, including education.

By her own accounting, those views have been profoundly shaped by her experiences as a beneficiary of public education, as a student at Thousand Oaks Elementary School in Berkeley and later at the Hastings College of Law (now called UC Law San Francisco).

Just three months ago, in remarks about college student debt in Philadelphia, she paid tribute to her late first grade teacher Mrs. Francis Wilson, who also attended her graduation from law school. “I wouldn’t be here except for the strength of our teachers, and of course, the family in which I was raised,” she said.

The most memorable moment in Kamala Harris’ unsuccessful 2019 campaign for president was in the first candidates’ debate when she sharply criticized then-Vice President Joe Biden for opposing school busing programs in the 1970s and 1980s.

“There was a little girl in California who was part of the second class to integrate her public schools, and she was bused to school every day, and that little girl was me,” Harris said in the first debate.

She was referring to Berkeley’s voluntary busing program set up in 1968, the first such voluntary program in a sizable city. Biden was apparently able to put the exchange aside when he selected her to be his running mate several months later.

It is impossible to anticipate what if any of the positions Harris took earlier in her career, or as a presidential candidate five years ago, will be revived should she win the Democratic nomination, or even become president.

But they certainly offer clues as to positions she might take in either role.

When she kicked off her campaign for president at a boisterous rally in downtown Oakland in Jan. 2019, she made access to education a major issue. “I am running to declare education is a fundamental right, and we will guarantee that right with universal pre-K and debt-free college,” she said. .

By saying education is a “fundamental right,” Harris addressed directly an issue that has been a major obstacle for advocates trying to create a more equitable education system.

While education is a core function of government — even “perhaps the most important function,” as Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling — it is not a right guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution. That has meant relying much more on state constitutions.

During her term as vice-president, she has played a prominent role in promoting a range of President Biden’s education programs, from cutting childcare costs to student loan relief.

Last year she flew to Florida especially to take on Gov. Ron DeSantis over his attacks on what he dismissed as “woke indoctrination” in schools. In particular, she was incensed by the state’s middle school standards that argued that enslaved people “developed skills that could, in some instances, be applied for their personal benefit.”

DeSantis challenged her to debate him on the issue – an offer she scathingly rejected. “There is no roundtable, lecture, no invitation we will accept to debate an undeniable fact: There were no redeemable qualities to slavery,” she declared at a convention of Black missionary women in Orlando.

Earlier in her career, she was best known on the education front for her interest in combating school truancy – an interest that could be extremely relevant as schools in California and nationally grapple with a huge post-pandemic surge in chronic absenteeism.

Students are classified as chronically absent if they miss 10 percent or more of school days in the school year.

Nearly two decades ago, while district attorney in San Francisco, she launched a student attendance initiative focused on elementary school children. Each year, she sent letters to all parents advising them that truancy was against the law. Prosecutors from her office would meet with parents with chronically absent children. If they did not rectify the situation, they could be prosecuted in a special truancy court – and face a fine of up to $2500 or a year in county jail.

By 2009, she said she had prosecuted about 20 parents. “Our groundbreaking strategy worked,” she wrote in an opinion piece in the San Francisco Chronicle, citing a 20 percent increase in attendance at the elementary level.

When she ran for attorney general in 2010, she backed a bill that enacted a similar program into state law. The law also subjected parents to fines and imprisonment for up to a year but only after they had been offered “support services” to address the pupil’s truancy.

This tough stance put her on the defensive when she ran for president, and she softened her position on the issue. She said the intent of the law was not to “criminalize” parents. And in her memoir The Truths We Hold: An American Journey, Harris described her approach to truancy as “trying to support parents, not punish them.”

During her presidential campaign five years ago, she made a major issue of what she labeled “the teacher pay crisis.” She said as president she would increase the average teacher’s salary by $13,500 – representing an average 23 percent increase in base pay. Almost certainly the most ambitious proposal of its kind made by any presidential candidate, the cost to the federal government would be enormous: some $315 billion over 10 years.

To pay for it, she proposed increasing the estate tax on the top 1 percent of taxpayers and eliminating loopholes that “let the very wealthiest, with estates worth multiple millions or billions of dollars, avoid paying their fair share,” she wrote in the Washington Post.

Also on the campaign trail, she proposed a massive increase in funding to Historically Black Colleges and Universities – one of which (Howard University in Washington D.C.) she graduated from. In fact, she proposed investing $2 trillion in these colleges, especially to train black teachers. She contended that if a child has had two black teachers before the end of third grade, they’re one third more likely to go to college.

Biden was able to push through a big increase in support for HBCUs totaling $19 billion – far short of her goal of $2 trillion.

Many of her positions on education – including a push for universal pre-school, and making college debt free – were aligned with those proposed by Biden, or ultimately implemented by him as president.

For that reason, there is likely to be continuity in her likely candidacy with much of the education agenda proposed by Biden.

But mainly as a result of lack of action in Congress and Republican-initiated lawsuits blocking his proposals, many of Biden’s campaign promises and programs, like making community colleges free and doubling the size of Pell Grants, remain unfulfilled.

It will now be up to Harris – and the American voter – whether she will have the opportunity to advance their unfinished education agenda.