Jackie Castillo was walking through her Mid-Wilshire neighborhood when she heard ceramic crashing against metal. She looked up to see orange terracotta tiles sailing down, one after the other, from the roof of a 1920s Spanish Revival home. The tiles whirled, twisting and turning like helicopter seeds or bird wings, before hitting the metal dumpster below. Castillo captured their descent on film, compelled by each tile’s momentary transformation into something vivid and alive just before its demise.

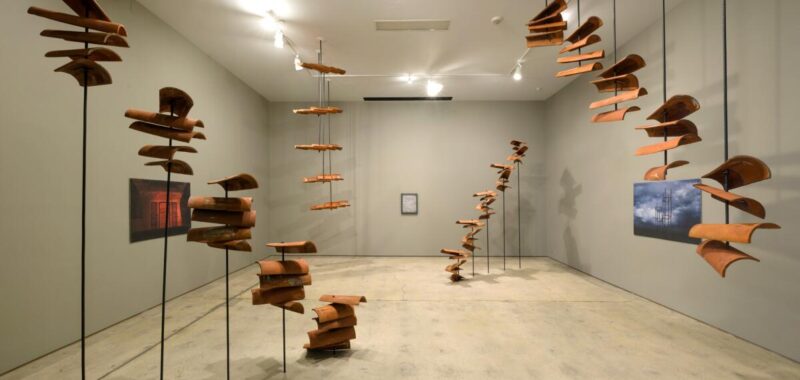

Eight years later, she has channeled that memory into “Through the Descent, Like the Return,” an installation on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art Los Angeles through August: Four groups of five steel reinforcing bars either ascend from the concrete floor or descend from the ceiling of ICA’s first-floor gallery. On each bar, five reclaimed terracotta tiles are arranged at various levels and angles, recreating the twists and turns from the film stills. To stand in the middle and view them in the round is to see how ruin and repair, falling and rising, are inexorably bound.

The daughter of Mexican immigrants, Castillo was born and raised in a working-class community in Santa Ana. She first discovered photography in a darkroom at Orange Coast College before completing her degree at UCLA.

“Taking photos is about reacting to the world and framing it, while developing them is a slow and tactile process,” she says. “It was my language, and I couldn’t stop once I understood that.”

Although photography is at the heart of her practice, she frequently merges filmic images with sculpture and installation, as exemplified by her show at the ICA as well as her recent USC master’s degree thesis presentation, which included mixed-media sculptures like “Between No Space of Mine and No Space of Yours,” a monochromatic photo of an abandoned lot printed on uneven stacks of cement pavers.

“From my first studio visit with Jackie, I was struck by the clarity and sensitivity she brought to her photography,” says ICA senior curator Amanda Sroka. “She’s both formally advancing her medium and adding a very human dimension to the larger arts landscape we find ourselves in.”

For Sroka, it was important to offer Castillo creative support and the opportunity to broaden the context for her commentary on land development and labor — especially given socioeconomic changes in the museum’s Arts District neighborhood. “In poignant and poetic ways, she reveals what’s erased and gives voice to what’s silenced,” Sroka says.

Jackie sought the support of her father, Roberto, who immigrated to the United States from Guadalajara in his 20s, with the conception and creation of the lilting terracotta and rebar sculpture. While her work has long centered on the visible and invisible labor of immigrant communities, especially as it pertains to the material and cultural history of urban environments, she still felt a disconnect between her life in Orange County and her artistic practice in Los Angeles, where she has lived for a decade.

“Making art has often felt like a very solitary pursuit, or questioning, and completely separate from seeing my family,” Jackie explains on the sunny afternoon we met at the ICA. “For this exhibition, I wanted to find a means to unite the two and spend more time with them along the way.”

Although Roberto’s electrical engineering degree didn’t transfer to the United States, Jackie grew up watching him build whatever the family needed. Roberto helped her determine the exact height and angle of each tile and to fabricate a means of securing them in place along the steel stake.

“I learned so much from our conversations about everything from aesthetics to mathematics,” Jackie says. “We think of artists as looking this one way, but given the space and the resources, it’s amazing what working-class people can do.”

The individual tiles and reinforcement bars create a striking impression of an enthralling and vertiginous centrifugal motion. “The exact sequencing of each stack corresponds to a fall captured in a film still,” she says. “They’re not arbitrary or merely aesthetic, but tied to a specific moment in time linked to a specific person’s body in an act of labor.”

By exposing the industrial rebar responsible for a building’s structural integrity, Jackie also draws attention to the workers responsible for the building’s construction, maintenance and repair. Beneath the facade of every home, school, business and community center lie layers of material meaning and memory that bear forth records of the minds and hands that envisioned and assembled them. The innumerable lives lived within their walls and the storms weathered from without leave lasting marks.

On the salvaged tiles alone, you can find salt efflorescence, water stains, fretting, lichen, smears of soot, scratches and gashes. Though the evidence may be imperceptible to the untrained eye, they also hold the memory of the earth from which they were formed and the traditional methods of molding and firing clay. That history is what gets lost when old materials are tossed in dumpsters and replaced with newly fabricated products.

Photographs incorporated into the installation recreate this layering effect. On the right side wall, an image of twin rebar pillars jutting up toward a brilliant cerulean sky is interrupted by the trace of hardly discernible letters and numbers. At first glance, the illusory text appears to be part of the photograph; on closer inspection, it becomes clear that it is on the cement board beneath the image, which is printed on a semi-transparent window screen. “I wanted to collapse or complicate the space where the photograph exists in these works,” Jackie says. “This way, they invite a more visceral engagement, requiring viewers to slow down to understand why the image seems to change depending on their perspective.”

The installation, as a whole, fosters a similar shift in perception. Standing at the center, I felt as though time had momentarily reversed, and I was witnessing the hand-molded tiles being passed up to the newly constructed roof.

Perhaps it is not too late to begin rebuilding differently, guided not by the technology and exploitative practices of the present, but by the craftsmanship and care of the past.