When Sean Baker was about to release his acclaimed “Anora,” he pondered the harsh reality of putting out an art-house movie — even a much-anticipated one — in 2024. “Sometimes I tweet about my film,” the writer-director told The Times in early October, “and the first question that comes back is: When will it be streaming?”

It’s a common lament. Terrific films abound, but the audience that once rushed to see them in theaters has shrunk. COVID-19 forced the temporary closure of multiplexes, but while spectacle-laden blockbusters have regained their pre-2020 mojo, indie movies still struggle to coax viewers to leave their homes.

Yet despite major obstacles, including the widespread shuttering of art-house-friendly theaters, some indies thrived this year, including “Anora.” And it wasn’t just because those films were artistically accomplished — it’s because inventive ad campaigns helped make them feel like events you needed to experience on the big screen.

As Christian Parkes, chief marketing officer for Neon, the studio behind “Anora” and the 2020 Oscar-winning “Parasite,” puts it, the trick is to “make [viewers] feel like you’re missing out on an important conversation if you’re not there opening weekend.” In 2024, Neon succeeded with two very different movies: the horror-thriller “Longlegs,” which grossed $127 million worldwide, and “Anora,” which rode its Palme d’Or win at May’s Cannes Film Festival to $29 million globally to date.

When Neon first met with “Longlegs” writer-director Osgood Perkins, Parkes’ team pitched a cryptic viral ad campaign that put viewers in the perspective of Maika Monroe’s detective, who seeks to unmask the enigmatic titular serial killer. “We give the audience these clues that they can piece together to unlock the mystery of the film,” Parkes explains.

That meant concealing the movie’s star, Nicolas Cage, who plays Longlegs, in the marketing materials. Provocatively, Neon designed a simple black billboard that featured an extreme closeup of an unrecognizable Cage alongside a telephone number and release date. Parkes hoped the curious would call the number, which led to a disturbing recording from Cage as Longlegs, but he didn’t anticipate the billboard’s seismic impact.

“The message was so creepy, people started pranking their friends,” Parkes recalls. “People were texting their parents: ‘Hey, Mom, I just got a new phone number. Can you call it and make sure that it works.’ And then [the parents] would call and then text them back, and be like, ‘I don’t know what that is — that’s terrifying!’ That thing took [on] a life of its own.”

While the “Longlegs” campaign cannily deemphasized its marquee name, the “Anora” ads pushed its biggest asset, using the tagline “A love story from Sean Baker.”

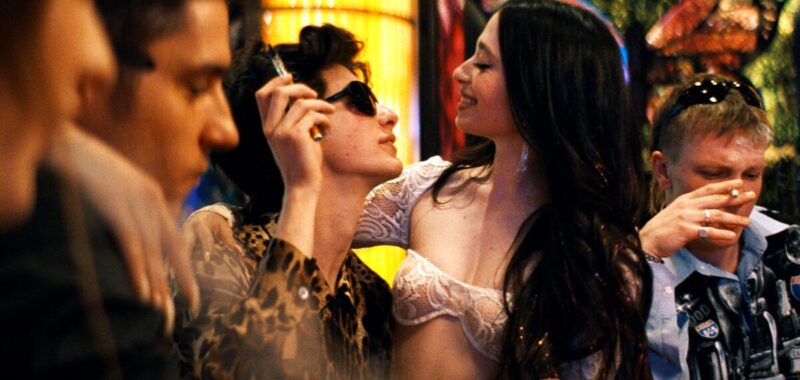

“Sean is his own genre,” Parkes says of the auteur behind “The Florida Project” and “Tangerine.” “He’s created his own world of movies. [‘Anora’] is a love story that only he could create. It became about tailoring that film in a way that would appeal to a young cinephile audience, the Letterboxd crowd.”

Part of Parkes’ rationale was that younger viewers have been receptive to returning to theaters since COVID, while older viewers have stayed away. “It’s very difficult to change consumer behavior,” Parkes says. “There’s a lost audience that isn’t going to come back. The older-skewing audience got comfortable staying at home.”

Which is why Jason Cassidy, vice chairman of Focus Features, is pleased that his company’s Oscar contender, “Conclave,” bucked the odds. On paper, director Edward Berger’s adaptation of Robert Harris’ novel, about the behind-the-scenes political maneuvering involved in selecting a new pope, seems exactly like the kind of grown-up drama that suffers at today’s art house. But the crowd-pleasing thriller has been a smash, collecting $31 million domestically to date.

Cassidy acknowledges that Focus, which releases more mainstream specialty fare such as “Downton Abbey,” wasn’t courting the same hip crowd that goes to “Anora.” “With this spectacular cast, they naturally lean older,” he says. But he believed that was a selling point. “[‘Conclave’] looks like one of those classic movies that’s going to deliver, for those older audiences, really juicy entertainment, giving them what they want. We call it a ‘familiar surprise’ — [people] want to have a sense of what kind of movie it is, but it’s something that overdelivers and surprises you.”

Consequently, Focus mounted a fairly traditional, old-fashioned art-house campaign, highlighting the film’s starry ensemble — including Ralph Fiennes, John Lithgow, Stanley Tucci and Isabella Rossellini — catchy premise and exotic Vatican setting. “I think about 77% of the [initial] audience was 35 years or older,” says Cassidy. “[We were] positioning it as the first movie to be seen as a real best picture contender. For those older audiences, being able to event-ize it helped it [become] a must-see for them.”

But once “Conclave” continued to hang around in theaters, younger viewers started seeing the film too — and then taking to social media, crafting parody mashups and stanning their favorite characters. “We saw it getting memed all over the place and loved it and certainly tried to lean into that,” Cassidy says. Focus’ social media accounts began retweeting the most popular memes, even creating their own based on users’ posts. “It helped connect it with the zeitgeist and fuel the success of the film.”

Myriad difficulties for art-house cinema remain, but “Longlegs,” “Anora” and “Conclave” demonstrate how savvy marketing can reach and mobilize discriminating viewers. For both Parkes and Cassidy, the challenges in the marketplace require specialty studios to get more creative in convincing audiences that smaller films are worth the time, money and effort to go to the theater.

Parkes sums it up succinctly: “If I’m going to get off the couch and pay my 15 bucks, give me something special.”