•Flynn steps away from his leadership position at a time of great uncertainty for Los Angeles’ 99-seat theaters.

•Under Flynn, Rogue Machine produced adventurous work by playwrights such as Samuel D. Hunter, Kemp Powers, Christopher Shinn and David Harrower.

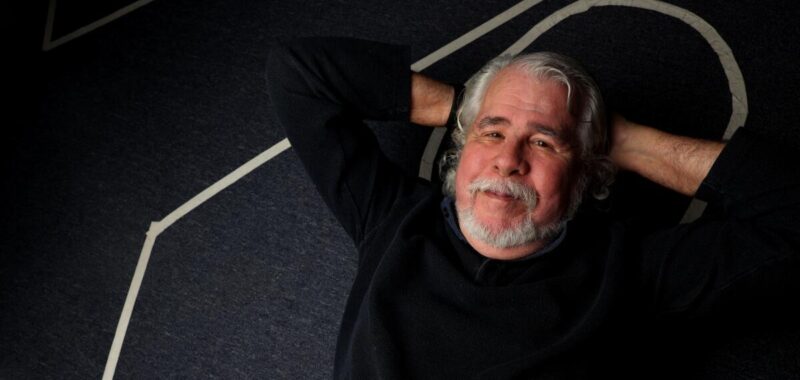

•The longtime TV producer and director speaks with his usual unfiltered candor on risk-averse big-budget theaters and this precarious period of transition in the field.

“Part and parcel of running a theater in Los Angeles is waking up two to four times a year and not knowing if you’re going to be in business the next week,” John Perrin Flynn reflected after announcing his retirement as producing artistic director of Rogue Machine Theatre.

Speaking at a desk on the set of “A Good Guy,” a new play by David Rambo that marks Flynn’s last directorial project in his current leadership role at the theater, he was addressing the state of the field, widely seen to be in a state of crisis since the pandemic. Despite that struggle, the company he co-founded in 2008 is one of the few in town that has been flourishing artistically since venues reopened.

Financially, Rogue Machine continues to operate by the skin of its teeth, but the cavalry has come in the form of a game-changing grant from the Perenchio Foundation and an anonymous philanthropic gift that will further shore up institutional stability. The theater isn’t out of the woods — theater is never out of the woods in Los Angeles — but it has been given an opportunity to build on its growing reputation and consolidate its gains.

So why then has Flynn decided to leave at the end of this season, his 16th? First and foremost, he knows the company is in excellent hands with artistic director Guillermo Cienfuegos, a prodigiously gifted director who has been part of the theater’s leadership team since 2018 and has been officially named Flynn’s successor. (Cienfuegos is the pseudonym actor Alex Fernandez has adopted as a stage director.)

Co-artistic director Elina de Santos, who spearheaded the theater’s playwriting programs for at-risk youth, is expected to continue. Justin Okin, another key leader, is taking over as full-time executive director. Flynn used to handle both the artistic and managerial sides of the job, an exhausting balancing act that perhaps explains his readiness to yield the reins.

“I’m 77, and the job is really thankless and difficult,” Flynn said with his usual unfiltered candor. “I was for 16 years working 60 to 80 hours a week, probably for no pay. I was not taking a salary. Once in a while, I would take a salary to direct or, when we did the musical “Come Get Maggie,” I took a salary to produce the show because that was somebody else’s project. They were more or less just hiring us. But it’s tiring always scraping by. It’s probably not as bad for theaters that have patrons with deep pockets. But for years we never had a patron on that scale. Sometimes it was my money that allowed us to continue, sometimes it was a friend’s. But the constant worry is debilitating.”

Flynn, who had a long career in television as a producer and a director before starting Rogue Machine, wanted to return to his theatrical roots. “I had finished a Lifetime series that I’d worked six years on,” he said. “There’s a lot to be said about that kind of employment. You make a lot of money and a lot of friends, but I was tired of it, and I wanted to go back to the theater.”

In 2007, he directed the Southern California premiere of Craig Lucas’ “Small Tragedy” at the Odyssey Theatre. The production was well received and he was eager to do more. He already had something in mind. On a whim, Flynn had answered an ad placed in a trade publication by an L.A.-based playwright who was looking for a director for his new script.

“I thought this was a silly waste of my time, but for some reason I was compelled to do it,” he said. “The play was ‘Lost and Found’ by John Pollono, and after I read it in one sitting I picked up the phone and said, ‘I’d love to direct your play. You’re an exciting young talent.’ And so we did that play as a rental at a venue on Santa Monica Boulevard.”

A formative collaborative relationship was born. Flynn, however, was dismayed to discover that theaters were reluctant to produce new work by unknown writers. One producer who wanted Flynn to direct at his theater told him, “Oh, I can’t do new plays. No one comes. I lose my shirt.” Flynn said he “got pretty much the same answer” everywhere.

Rogue Machine was born precisely out of this need to present daring new work that wasn’t finding a home elsewhere in the city. The vacuum left by the nonprofit behemoths, who in Flynn’s view have largely abdicated their responsibility, created an opportunity, a place to showcase the works of such intrepid writers as Samuel D. Hunter (“A Bright New Boise” and “Pocatello,” among others), Christopher Shinn (“Dying City”), David Harrower (“Blackbird”) and Enda Walsh (“The New Electric Ballroom,” “Penelope”).

No one has a better claim of being Rogue Machine’s house playwright than Pollono. His play “Small Engine Repair” helped put the company on the map. A long-running hit at Rogue Machine, the play was subsequently produced off-Broadway, where Charles Isherwood in his New York Times critic’s pick review compared Pollono to Martin McDonagh.

“I’m surprised Mr. Pollono hasn’t already been snapped up by the hungry maw of television,” Isherwood presciently remarked in an aside. More than a decade later, two of Pollono’s plays that had their start at Rogue Machine, “Small Engine Repair” and “Razorback” have been adapted to the screen. (“Riff Raff,” based on “Razorback,” premiered this fall at the Toronto Film Festival with a cast that includes Jennifer Coolidge, Gabrielle Union, Pete Davidson, Ed Harris and Bill Murray.)

Flynn himself marvels that a small L.A. theater with a shoestring budget could help launch a major career. He points to Kemp Powers’ “One Night in Miami…” as another instance of Rogue Machine being the little engine that could. The play, a fictional take on the night Muhammad Ali, Malcolm X, Sam Cooke and Jim Brown gathered in a hotel room in 1964 and exchanged heated views on the Civil Rights struggles, premiered at Rogue Machine before enjoying a successful run at London’s Donmar Warehouse. A widely praised film version, directed by Regina King, was released in 2020.

Rogue Machine plays come in several varieties. Flynn is open to the Beckettian experimentation of Walsh’s “The New Electric Ballroom,” a play he decided to produce after seeing an international company perform the work at UCLA Live and believing that he could offer Los Angeles audiences a different way inside the drama. A play like Harrower’s “Blackbird,” too morally disquieting to be produced by the city’s risk-averse big-budget theaters, appealed to Flynn’s heterodox side. Hunter’s spiritually searching plays offering acute portraits of red state America appealed to Flynn’s metaphysical and sociopolitical sides.

The absence of women playwrights in this summary mirrors the absence of women playwrights on the list of favorite productions Flynn included in his retirement letter to the company. Rogue Machine has taken strides to diversify its programming, but a persistent gender gap in playwriting signals a problem that will have to be redressed by Cienfuegos and his team.

Developing L.A. voices, Pollono and Powers among them, has been integral to the theater’s mission. Rogue Machine has provided a nourishing community to playwrights through workshops, salons and educational outreach. Flynn said that his mandate all along has been to produce world premieres along with plays that are new to Los Angeles.

Occasionally, Rogue Machine has produced some clunkers, head-scratchers like the musical “Come Get Maggie” or plays that just weren’t ready for prime time. Are these occasional flops simply the cost of doing new work?

Flynn admitted that there are many factors at work. Sometimes there are personal relationships involved and sometimes there are financial incentives that allow the theater to produce at a time that it would otherwise be dark. But it’s always a disappointment, he said, when the art doesn’t come together.

When you’re worried about making the rent — and Rogue Machine has moved around a lot — you’re not always going to live up to your ideals. After establishing its reputation at Theatre Theater, the shape-shifting venue on Pico Boulevard with a flexible black box that housed some of the company’s most memorable offerings, Rogue Machine moved to the MET Theatre on Oxford Avenue before heading out to the Electric Lodge in Venice.

In 2021, Rogue Machine moved to its current home at the Matrix Theatre on Melrose Avenue. Cameron Watson’s pitch-perfect 2022 production of Daf James’ “On the Other Hand, We’re Happy” inaugurated what has been one of the brightest periods in the company’s history. Last year’s L.A. premiere of Will Arbery’s “Heroes of the Fourth Turning,” sensationally directed by Cienfuegos, was one of the best things I’ve seen anywhere since theaters reopened.

Were it not for Flynn’s leadership, L.A. theatergoers would have been deprived of local introductions to some of the most innovative talents in contemporary playwriting. While the Mark Taper Forum, Pasadena Playhouse and the Geffen Playhouse fretted about the taste of their least adventurous subscribers, Rogue Machine reminded us that theater is most alive when misbehaving.

“Los Angeles played an important part of the regional theater movement in America,” he said. “But there’s been a calcification of the larger theaters. They are afraid to do important work. Before the pandemic, Center Theatre Group, which was already in trouble, spent more than $40 million on a season that included a number of touring productions. Our culture is stuck in these old habits of thinking. I have a horse in the race, but imagine if that $40 million went to eight smaller theaters. Imagine the kind of artistic boost that could happen.”

One lesson that Flynn draws is knowing when it’s time to get off stage. “[Center Theatre Group founder] Gordon Davidson stayed at the party about five years longer than he should have,” Flynn said. “And the Taper has never recovered. There was a time when Gordon could have had Oskar Eustis take over. Oskar was here. Oskar was his protege. What would that have meant to Los Angeles?”

Eustis made history of his own at New York’s Public Theater, where “Hamilton” emerged under his watch. But Los Angeles theater is poised for a renaissance, with Danny Feldman at Pasadena Playhouse, Snehal Desai at CTG and Tarell Alvin McCraney at the Geffen Playhouse all determined to turn the page on a lackluster last decade, characterized by unfulfilled potential, dwindling audiences and watered-down missions.

Flynn acknowledged that we’re in a precarious period of transition. Precarious not just because of the budgetary realities but also because of the need for structural and audience renewal. The old models aren’t going to save us. Each generation, he believes, must find its own way to reestablish the art form’s institutional vitality.

When asked which theaters Flynn sees as peer organizations, he doesn’t trot out communal news releases but answers succinctly: Echo Theater Company. Both theaters, he said, are looking for “the kind of work that needs to be put before the public so the public can experience it and question whatever the play is bringing up.”

Flynn often compares notes with Echo Theater Company artistic director Chris Fields who similarly struggles to get the rights to plays that agents are reluctant to bestow on small L.A. theater companies, no matter how superior they may be to their larger counterparts. There’s agony on Flynn’s face when he talks about plays by McDonagh and Annie Baker that for one reason or another proved elusive.

“I’m always looking for a play that exposes the human condition,” he said. “Who are we? What are we doing here? How did we get here? Where are we going? The kinds of issues that reveal the complexity of life. The question of what is good, because good is not easy. It’s not black and white.”

Maybe one of the reasons playhouses of integrity are having such a difficult time is that we’re living in an era when schematic thinking has taken over. Social media has ingrained in the public a habit of ideological certainty that playwrights worth their salt know is a lie.

On offer now at Rogue Machine is the world premiere of Rambo’s “A Good Guy.” The drama, which is being performed upstairs at the Matrix in the cozy hideaway of the Henry Murray Stage, examines the old right-wing saw that a good guy with a gun somehow makes us all safer. It’s an appropriate last play for Flynn to direct in his role as the leader of a theater committed to showing us our collective countenance, warts and all.

Flynn deserves a break from his heroic theatrical labors, but he’s not done yet. He’ll continue to direct at the theater when the spirit and the playwright move him. And Cienfuegos promises to build on what is already an extraordinary legacy, making Rogue Machine the inclusive, intimate center of hard-hitting playwriting that L.A. deserves.