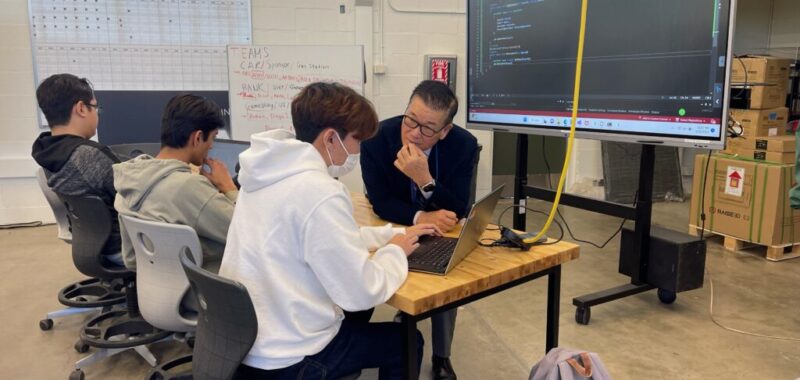

Superintendent Michael Matsuda speaks with students in a technology classroom in Anaheim Union High School District.

Courtesy: Anaheim Union High School District

The demise of great corporations like Kodak, Sears and others serves as a stark reminder of the perils of failing to innovate and evolve with consumer demands. Kodak famously ignored the rise of digital cameras despite inventing the technology itself. Similarly, Sears, once a retail giant, failed to adapt to the changing landscape of e-commerce. These cases highlight a common theme: success breeds complacency, whereby nimble competitors can quickly exploit new technologies and consumer trends.

Will public education, ensconced in outdated brick-and-mortar buildings and traditions, be next?

The pandemic forced schools to close but did not necessarily stifle learning. New models of teaching, such as neighborhood learning pods run informally by local parents, called “microschools,” were created. These microschools, many now monetized for profit, have grown exponentially, serving over 1.5 million K-12 students, mostly unregulated and taught by noncertified, noncertificated “teachers.” The jury is still out on this new model, but, in the meantime, microschools are gaining momentum with parents who want more choices for their children.

Arguably, the rise of microschools poses a significant threat to the traditional public school system, challenging its long-standing dominance in the American educational landscape.

Microschools, with their aggressive marketing to adapt quickly to the evolving needs of students and families, offer a “fresh” approach to education that starkly contrasts with the bureaucratic, often stagnant nature of public schools. As microschools grow in popularity, they expose the deep-rooted issues within the public education system, particularly its resistance to change and reliance on traditions tethered to a “teach to the test” culture making schools mostly unengaging and irrelevant to students’ lives.

According to a recent article in Politico, startup companies backed by investors like Sam Altman, chief executive of OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, act as the support system for teachers running microschools by handling issues like leasing classrooms, getting state approval and recruiting students. One such startup, Primer, recruits the “top 1 percent” of teachers and pays them 25% more than they would make on a school district salary. The company also offers teachers a revenue share for bringing in more students, treating them as “entrepreneurs.” It doesn’t currently operate in California, but is planning on expanding to more states.

Microschools, which typically serve small groups of students in personalized learning environments, have gained traction as families seek more flexible and tailored educational options. This flexibility is particularly appealing in an era when traditional education models are increasingly seen as one-size-fits-all, leaving many students either unchallenged or overwhelmed.

One strength of microschools is their ability to innovate rapidly. Unlike public schools, which are often bogged down by layers of bureaucracy, microschools can implement new teaching methods, curricula and integrate technologies quickly. This agility allows them to meet the needs of students who may not thrive in a traditional classroom setting, such as those with learning disabilities, gifted students or children who simply learn better outside the confines of a traditional school day.

However, without regulation or oversight, uninformed parents and students may be shortchanged in that classes are often not taught by well-prepared certificated teachers (who are more likely to be steeped in the science of learning and development) and schools may exclude students who do not “fit” into the model, thereby leading to more segregation and “otherness” — not a good outcome for society. Unfortunately, because of a lack of accountability, it is unknown whether microschools are meeting their student learning outcomes or preparing students for college and career readiness.

In stark contrast to the nimble nature of microschools, public schools are often viewed as educational behemoths — large, slow-moving institutions that struggle to adapt to the changing needs of students and society. This inflexibility is rooted in the very structure of the public education system, which is designed to serve large numbers of students in a standardized manner, which is seen as outdated in a world that demands more personalized and flexible approaches to education.

Furthermore, the bureaucratic and compliance-driven nature of public schools often stifles innovation. This makes it difficult for schools to implement new ideas or respond quickly to the needs of their students. In contrast, microschools, which are often run by small teams of educators or even parents, can make decisions quickly and adapt to new challenges as they arise.

The growing popularity of microschools represents a significant threat to the traditional public school system. As more families opt for microschools, public schools may find themselves facing declining enrollment, which could lead to reduced funding and resources. This, in turn, could exacerbate the challenges that public schools already face, such as overcrowded classrooms, insufficient funding, and a lack of access to modern educational tools and technologies.

Moreover, the growth of microschools highlights the shortcomings of public schools and puts pressure on them to reform. As parents and policymakers become increasingly aware of microschools, they may demand more flexibility, choice, and innovation from the public education system.

The threat posed by microschools is not just a challenge to the public education system, but also an opportunity for redesign and reform. If public schools are to remain relevant in the face of growing competition from microschools, they must find ways to become more flexible, innovative and responsive to the needs of their students. This may involve rethinking traditional methods of instruction, reducing bureaucratic obstacles, and placing a greater emphasis on personalized learning augmented by technology.

There are a number of obstacles to innovation. One is the difficulty in shifting from a traditional “seat based” instruction, tethered to the old Carnegie unit of attendance, to more “work-based” instruction to support internships, mastery grading and flexible scheduling. Another requires a mind shift beyond a top-down standardized test culture to teaching to the “whole child” with a focus on relevance and engagement.

As microschools continue to grow in popularity, public schools must either find ways to innovate and meet the demands of today’s students or risk becoming increasingly irrelevant in the rapidly evolving educational landscape.

•••

Michael Matsuda is superintendent of Anaheim Union High School District.

The opinions in this commentary are those of the authors. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.