*

Article continues after advertisement

Priscilla Gilman: Tell me about how and why you decided to tell the story of your mother’s life in reverse, beginning with her death in the early days of the COVID pandemic. What challenges did that structure pose and what possibilities did it enable? How did you choose which “chapters” in your mother’s life to set your chapters in? What did you leave out and why?

Jill Bialosky: For many years, I knew I wanted to tell my mother’s story. I wanted to preserve a period of history through the narrative of an extraordinary woman and the family she made under extreme circumstances, to capture what life was like for a woman of my mother’s milieu. I knew my mother’s story and what was at stake would resonate with others. But how? My mother passed away during the first month of COVID, and because of quarantines, I couldn’t see her as she was dying, nor was I able to go to the graveside funeral since I was in New York and my mother was in Cleveland.

I began to write about her from the present perspective, of witnessing her funeral on FaceTime with my sister in Cleveland during those surreal months of Covid, and then writing about her life when she was suffering from Alzheimer’s, where I witnessed the toll the slow progression of the disease took from her. I was reading T.S. Eliot’s “Four Quartets” and there are the lines I use as an epigraph in my book, “What we call the beginning is often the end./And to make an end is to make a beginning. / The end is where we start from.” It occurred to me that telling my mother’s story from the end to the beginning would allow the reader to see her slowly coming alive through pivotal periods of her life. I responded to Eliot’s sentiment that for all of us on our journey through life, the beginning is always at the end and the end is the beginning. Organically, it made the most sense for me to tell the story this way and for the book to land at the beginning when my mother was first born. Writing the book this way kept her alive for me.

PG: You thread references to and excerpts from literature throughout The End Is The Beginning in a surprising, illuminating, and enriching way. Novels from Forster’s Howard’s End to Mann’s The Magic Mountain, poems from Yusef Komunyakaa’s “Blue Dementia” to Dickinson’s “I heard a Fly buzz-when I died” become touchstones or talmuds, companions or lodestars for you as you grapple with guilt, grief, bewilderment, anxiety, longing. What did these texts and authors offer you while living through your mother’s decline, grieving her death, and writing this book? How can fictional characters help us to better understand the real people in our lives? (remember the “40 Characters in Search of My Father” from The Critic’s Daughter!). How has literature served as an escape, a portal, a doorway to a larger life for you as a young girl, as a college student, as a young editor, as a writer attempting to make sense of the loss of your sister, your baby, your mother?

JB: I do remember your “40 Characters in Search of My Father” in your beautiful book, The Critic’s Daughter, about your father. As I was writing The End Is The Beginning, I thought of your book, especially the challenge of bringing a parent alive for the reader. It’s personal, and yet, the art of storytelling, the art of this kind of personal writing, is to tell a story you hope will be universal. It’s a tricky undertaking. The texts I cite were indeed Talmudic as I was writing the book. It was coincidental that I was listening to Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, while I was writing about my mother’s years in an institution, and aspects of that monumental novel made me consider the mysterious nature of time, memory, and institutional life. How does life change when our surroundings change?

Certain poems became lodestars, as is my way, and Dickinson’s especially. She is the poet of eternity, of immortality and writing is a way of defying mortality. Literature has indeed served me as a portal. In my book, Poetry Will Save Your Life I share how pivotal poems in my coming of age served as ways of understanding the universality of our most private experiences. As a lifelong reader, I appreciate how characters in literature, and their circumstances, even from centuries past, mirror our own lives. I would be lost without literature. It is a lifeforce.

PG: How did the social histories and reported memoirs you read, from Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique to Andrew Solomon’s The Noonday Demon, give you a deeper perspective on and context for your mother’s experience?

JB: The Feminine Mystique was an important work for me to understand women’s lives in my mother’s generation. How they viewed themselves and how the patriarchy kept them in the closet, so to speak. My mother’s life was shaped by this period when women were expected to be wives and mothers, and sexual objects. My mother couldn’t find her way out of this trap when tragedy struck, and at age twenty-five, she lost her husband suddenly and, without a livelihood, was left to care for three daughters under the age of three.

My mother struggled with episodes of depression, and when I was coming of age in the 1960s and 70’s, depression was not fully understood or spoken about. It was something to keep under the rug. It wasn’t until books like William Styron’s Darkness Visible and then later The Noonday Demon by Andrew Solomon that the silence was broken, and I fully understood that depression was a severe disease. I used to feel frustrated by my mother when she was depressed. I didn’t know that it wasn’t something she could fully control. These works are landmarks.

It wasn’t until books like William Styron’s Darkness Visible and then later The Noonday Demon by Andrew Solomon that the silence was broken, and I fully understood that depression was a severe disease… These works are landmarks.

PG: Did you write as you lived? In other words, did you journal, send long emails or texts to your sisters or your husband, take notes as you experienced aspects of your mother’s situation? How much material did you produce all along the way and how did you gather and stitch together that material into one coherent memoir?

JB: I’m not a journal writer. I make notes in a notebook when I’m working on a book or make notations in the notes tab on my iPhone, sometimes gathering quotes from films or books I’m reading. I relied on memory, lived experience, stories my mother, my sisters, or other relatives or friends told me about my mother and her family before I was born, photos, scrapbooks, and research to evoke the milieu of my mother’s life. I wrote the book chapter by chapter and through many rounds of rewriting, I aimed to capture what I perceived as my mother’s consciousness and being.

PG: What advice would you give other memoirists about how to best capture, honor, and memorialize a lost loved one while being true to the complexity of their being and the essential unknowability of any person?

JB: To stay true to what you know and intuit no matter how painful or challenging and to keep in mind that personal writing is subjective, you can only write from your own experience and vision.

PG: What did your experience with your mother, her battles with depression and Alzheimers, and the many losses she suffered, from her beloved first husband to her youngest child, teach you about memory and forgetting, loss and recompense, the nature of identity, the art of losing?

A memoirist’s task is evoking and capturing… so that the reader can enter the space.

JB: The art of losing, a phrase from the brilliant poet Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “One Art” comes to mind reading your question. The poem records the art of losing first keys, then places, and then names, until finally, the poem lands on losing a loved one. The poem concludes, “Even losing you…. I shan’t have lied. It’s evident/the art of losing’s not too hard to master/though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.” Are those lines meant to be ironic? Can we ever master the art of losing someone? My mother surely had practice. In my book, I write that one loss opens others. My mother kept her many losses close. Even though she only had my father with her for six or seven years, his memories and love sustained her until the end of her life. She always felt she’d be reunited with her loved ones in the afterlife. Her last days she still twirled her engagement ring my father gave her on her finger. People we love are always with us, even after they’ve departed.

PG: Over the course of this memoir, the house your mother raised you and your sisters in becomes a distinctive and endearing character in its own right. We walk through its rooms with you, smell its aromas, imagine its inhabitants at various ages and stages. What did that house mean to you? to your mother? What did having to sell it do to you, your mother, your sisters? How is evoking and capturing a place central to the memoirist’s task?

JB: Yes, the house on Lytle Road is indeed a character in my book. I haven’t lived in that house in decades, but I can still remember every creek and crevice. The house was my mother’s canvas. Her eye for vintage finds from Flea markets and antique stores was extraordinary, and she enjoyed making the house her own artistically. My childhood was in that house; it stood by us and kept us whole through many manifestations; so many of my memories reside there. My sisters and I had to sell it once we moved our mother into assisted living. I thought my mother would be devastated and nostalgic to leave it, but she wasn’t.

At that point in her life, she recognized that she couldn’t live there alone anymore. The hardest part in selling the house was going through all the memorabilia. It broke my heart. A memoirist’s task is evoking and capturing, as you say, so that the reader can enter the space. The details and sensations give the reader a picture and make the work come alive. I read that Keise Laymon said to his students working on memoir, that they should take a fiction class to learn how to create scenes. I couldn’t agree more.

PG: What did you inherit from your mother? What about her lives on in you and your sisters?

JB: I like to think I inherited my mother’s kindness, love, warmth, and empathy. I realized, while writing this book, how deep motherhood is and how so much of my being is shaped by my mother. I might quarrel with Philip Larkin’s famous lines in his poem “They be the Verse: “They fuck you up, your mum and dad./ They may not mean to, but they do./ They fill you with the faults they had/ And add some extra, just for you.” On the contrary, my mother’s inabilities, shaped by her coming of age, instilled in me strength and the determination to be independent.

_______________________

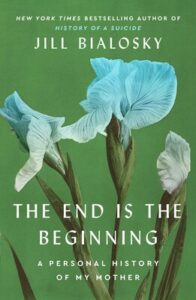

Jill Bialosky’s The End Is the Beginning: A Personal History of My Mother is available now from Washington Square Press.