It was a mere 25 years ago that “The Sopranos” debuted on HBO and set the clocks to zero on what some like to call television’s Platinum Age.

Alex Gibney’s two-part scrapbook documentary “Wise Guy: David Chase and the Sopranos,” premiering Saturday, again on HBO, is, among other things, a sort of a triple profile of creator Chase, star James Gandolfini and their mutual creation, New Jersey “waste management consultant” — i.e., mobster — Tony Soprano. In that knowledge of “The Sopranos,” its premise and characters is taken as assumed, it’s not a film for newcomers. But it should appeal to anyone interested in the inspirations, decisions, revisions, sweat and serendipity that go into making a series so critically lauded that “Saturday Night Live” parodied the reviews (“‘The Sopranos’ will one day replace oxygen as the thing we breathe in order to stay alive.”)

What made “The Sopranos” rare if not unique was the amount of freedom the show was given. It wasn’t the earliest creator-driven series — “Ozzie & Harriet,” written and directed by its star Ozzie Nelson, preceded it by 47 years, and “The Larry Sanders Show,” HBO’s first great series, was very much an unalloyed expression of Garry Shandling’s vision. But its massive success undoubtedly empowered future showrunners and shaped conversations in executive offices. It opened the door to similar series that might never have been pitched or greenlighted otherwise — “Ozark,” “Animal Kingdom,” “Breaking Bad” — and inspired a rage for antiheroes from which television has not yet recovered.

What also distinguished the show was that it was personal. No “Sopranos” fan is unaware of the fact that Tony’s nightmare of a mother, Livia (Nancy Marchand), is based on Chase’ own. (“I trust that this creature I’m portraying is deceased?” Marchand said.) The series not only borrowed from Chase’s life — the Sopranos lived in one of the neighborhoods where Chase grew up — but asked the writers to reach into the darker, weirder parts of themselves and their past. Describing the writers room, Robin Green admits, “We could have been mistaken for being racist, sexist, you-name-it-ist.”

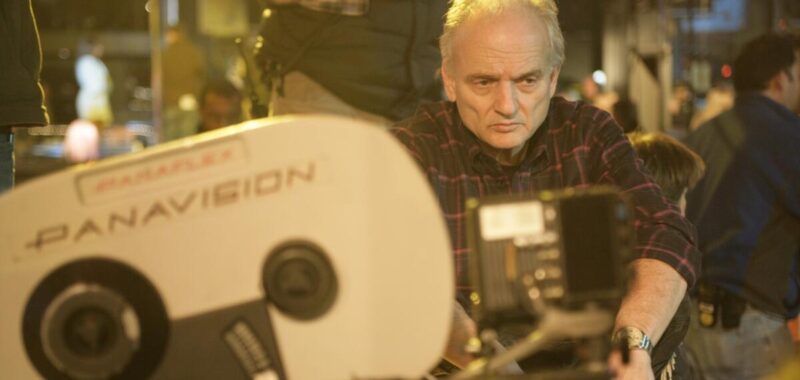

There are the usual features that make “making of” documentaries, of which this is a rather grand example, attractive — audition tapes, films of the filming, amusing anecdotes, historical photos and footage. Gibney’s idea to interview Chase on a replica of Dr. Melfi’s office from the series, putting himself in the therapist’s chair, is a little too on the nose, perhaps, but not inappropriate to the reluctant, ultimately forthcoming subject. “I didn’t realize this was going to be about me,” Chase says, and, “Seriously, I don’t know about this,” and soon, “I’m talking too much.” Other commentators, including actors Lorraine Bracco, Michael Imperioli, Drea de Matteo, Steven Van Zandt and Edie Falco, and HBO executives Chris Albrecht and Carolyn Strauss, describe a sometimes difficult, if much admired, boss from the outside.

We also get a look at Chase’s Stanford student film, “The Rise and Fall of Bug Manousas,” in which gangsters in 1940s clothing sport ‘70s long hair and mustaches — which is to say, very much a ‘70s student film. “We thought we were doing Godard,” Chase relates. “I don’t know what we thought Godard was doing, but we weren’t doing it.” After work on some sub-Corman exploitation films, he made his way to television, where though successful — he was staffed on “The Rockford Files,” “I’ll Fly Away” and “Northern Exposure” — he was unsatisfied: “The problem was, you knew what the limits were but you were always testing them, and you would always fail.”

When HBO picked up “The Sopranos,” he says, “It was like I had been in the middle of a terrible ocean and I had landed on a desert island, a beautiful, palm-colored island. I thought, my life is saved.” On the big screen, films that placed gangsters, and specifically Italian gangsters, at the center of the story were nothing new — “The Godfather,” “Goodfellas” and “Casino” had all been released. And “The Sopranos,” which began as the script for a feature film, had cinematic ambitions.

The pilot, in which Tony, having become depressed after a family of ducks living in his swimming pool takes off, sending him reluctantly to therapy, was exciting to me — I loved the idea that a villain might learn something about himself, that the sort of character usually portrayed as static could develop. Well, I was mistaken. That never happened. (Therapy, Chase says, didn’t make him a better man, just a better mobster.)

Because most of us got to know him as Tony Soprano before we ever met the actor, Gandolfini comes across as almost shockingly sweet. Much of the second episode is devoted to him, the toll of living inside Tony, or Tony living inside him, and of the long hours the part required. “I walked in with a big smile on my face and I got punched right in the nose,” he tells an interviewer. When he negotiated a $1 million per episode contract with HBO, he gave $30,000 checks to his castmates — apart from Falco, who appears to be hearing this story for the first time — but also agreed to be docked $100,000 for every day of work he missed, of which there were more than a few. Before assessing the infamous finale, Gibney jumps forward to Gandolfini’s memorial — he died in 2013 at 51, six years after the series ended — and Chase’s moving eulogy.

Regardless of the series’ quality, I had burned out on Tony and his crew some time before the end — though I watched it until the end and the infamous moment when the screen went black, as Tony looked toward the door of the diner where he was meeting his family — a non-ending director of photography Alik Sakharov calls “a resolution of irresolution.” Despite Chase having indicated at times that this was a death scene, it’s not a question he, or anyone else interviewed, cares to answer here. (Van Zandt has a stock answer: “What happened was the director yelled cut and the actors went home.”) For all that Tony deserved his karmic comeuppance, I happily remain in that ambiguous space.

The show was extensively reported upon during its run and afterward, and there is probably little here that hasn’t been expressed elsewhere. But this is film, and Gibney repeatedly juxtaposes the artist’s lives with examples from the show. It can seem a little facile, as it often does when you analyze the art in terms of the life, but it’s also fairly persuasive. Analysis of the show, by Chase and others, is thorough, sometimes surprising — the staging of the finale was influenced by “2001: A Space Odyssey” — and sometimes poetic. You may not have grasped the importance of the lyric, “The movie never ends, it goes on and on and on and on,” from Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’,” which plays through the last scene, but it illuminates that abrupt black screen.

“You may not go on,” says Chase, “but the universe is going to go on, the movie’s going to keep going.”